Tuesday, February 28, 2006

Goldmine Shithouse - The Clown Flippers

Thursday, February 23, 2006

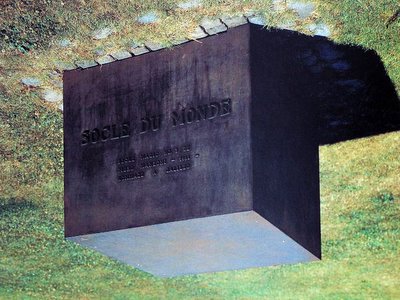

I'm not sure

what this is, but I like it.

link

The Finger

And the following picture (The Red Ball No.1 (2000)), by Loretta Lux, is a counterbalance.

Oh, how I love the static taste of play!

(via)

Wednesday, February 22, 2006

The No.8 Wire - Issue 63

Tuesday, February 21, 2006

Is a Fake Pollock Better?

- asks Don Foster in a recent article in N.Y.Times.

May not a Pollock forgery that passes for authentic be the best Pollock of all?

Here is a more of the article, which will soon be unavailable for free reading:

LAST year, 24 paintings were unveiled as previously unknown works by Jackson Pollock. (...)

But Richard Taylor, a physics professor retained by the Pollock-Krasner Foundation to subject six of the paintings to computer-assisted analysis, discovered that the paintings may well be fakes — at least, the drips lack Pollock's characteristic geometric pattern. The collection's owner disputes that this finding is conclusive.

At the heart of the controversy lie critical questions about artistic meaning and value that have vexed literary scholars no less than art historians. Would the exposure of a hitherto successful forgery diminish Jackson Pollock's reputation as a unique creative genius, by demonstrating that his work is replicable? If Shakespeare were credited with a mediocre poem hitherto presumed to be written by a lesser light, would that change our opinion of Shakespeare?

"What matter who's speaking?" asked Michel Foucault, quoting Samuel Beckett.

What matter whose painting? The implied answer — no matter at all — takes for granted that cultural artifacts are symptomatic of the society that produced them. The critic's job, then, is to assess the product on its own merits, quite apart from the artist's name or reputation. If "Hamlet" had been written by Christopher Marlowe or Edward de Vere, not by William Shakespeare, would the text therefore be less great? Perhaps not, but we would think of it in a different way.

If a previously authenticated Pollock painting was actually done by a disciple, or by Norman Rockwell, or by a monkey with a paintball gun, yet looks to be authentic Pollock, so what? The look-alike might be worth less at Sotheby's, but would it be worth less as art?

At stake in such attributional debates is a question of methodology: how can experts tell the difference between the real thing and an imitation? If the qualitative judgment of Pollock or Shakespeare scholars differs from quantitative analysis of a computer-assisted study, whose verdict will carry the day? That Richard Taylor's analysis can inform us of patterns generated by Pollock much of the time provides no guarantee that Pollock reproduced those patterns all of the time. But if the Pollock canon includes a forgery, it may be that Taylor's analysis provides a more objective mode of analysis than aesthetic appreciation.

(...)

In the art world, the problem of attribution is complicated by market value.(...) if you have paid, say, a half-million for a Pollock painting and some physicist and his computer say that you were hoodwinked, the question of the work's value is not wholly aesthetic.Literary and art attribution is not just a game of pin the name on the donkey. A community of interested scholars must consider all available evidence, and come to a consensus. In the case of the Pollock canon, the jury is still out. It would be a mistake, in my opinion, to sell the disputed Pollock canvases at a discount without more evidence than computer-assisted analysis of drip patterns.

Meanwhile, Jackson Pollock may be chuckling in his grave: if the object of Abstract Expressionist work is to embody the rebellious, the anarchic, the highly idiosyncratic — if we embrace Pollock's work for its anti-figurative aesthetic — may faux-Pollock not be quintessential Pollock? May not a Pollock forgery that passes for authentic be the best Pollock of all?

Well, may it not? This question joins the recent Duchamp controversy and many, many other cases where an artist's desire for artistic freedom seems to be forgotten when his works are judged by computer programs or valued for their size, or put on a pedestal and turned untouchable.

There is one factor, however, that tends to be forgotten in all our excitement about the real meaning of art and its heroes. I mean psychology of art. Namely, two points about it:

1) As art viewers, we feel the need for coherence. The work has an artist, the artist has an identity, the identity is not just some drips of paint scattered across the canvas of the soul, but it is a whole, it makes sense. In this case, it means a) Pollock was a painter; b) Pollock was a good painter; c) Pollock's paintings are related to a) and b); finally, d) we can expect that Pollock's work can only be his (there are recognizeable patterns, then).

This final point is the most questionable, and obviously we often fail at it, misjudging a work, attributing it to the wrong painter, etc. But our failures are only more proof of the possibility of success. And if we wish to name some of the 20th-century works of art that are based on "anonimity", such as Yves Klein's exhibition of air, we must notice that they were conceptual works of art, and we are ready to pay either for the event (as a performance of burning money), or for the signs of the concept (as the partiture of Cage's 4'33). The silence, the air, we somehow don't actually assign to the artist. Earth, after all, is not Manzoni's.

2) Reality check: artists aren't always right. Not even about their own work. Pollock might have dreamed of " the rebellious, the anarchic, the highly idiosyncratic", but he never moved beyond the canvas (he never even made the tiniest hole in it, as Fontana ever-so-modestly mentioned). Artists say a lot of things. And dream of even more. That's our job. If we don't dream, something is wrong. As Jules Verne put it, there are no great achievements without exaggerated expectations. But if this is true, we simply cannot take the artist's word for it. Or at least, we don't need to. Not even when they're dead and famous (what a scary combination!). That's why we might just pay more attention to our way of seeing The Fountain, or a drip painting, than to that of the artist. After all, if we listened to the wonderful, charming futurists, we wouldn't even know them.

2) Reality check: artists aren't always right. Not even about their own work. Pollock might have dreamed of " the rebellious, the anarchic, the highly idiosyncratic", but he never moved beyond the canvas (he never even made the tiniest hole in it, as Fontana ever-so-modestly mentioned). Artists say a lot of things. And dream of even more. That's our job. If we don't dream, something is wrong. As Jules Verne put it, there are no great achievements without exaggerated expectations. But if this is true, we simply cannot take the artist's word for it. Or at least, we don't need to. Not even when they're dead and famous (what a scary combination!). That's why we might just pay more attention to our way of seeing The Fountain, or a drip painting, than to that of the artist. After all, if we listened to the wonderful, charming futurists, we wouldn't even know them.I suppose if we join the dots 1) and 2), we see that the artists need a story and we need one. Trying to make us forget any story and see the "pure drip value" of a Pollock seems absurd. On the other hand, promoting the avant-garde tendency towards anarchy as a way of promoting the very artists that lived this tendency is, well, silly. Damn it. We actually need the library, and we need the museum. And some of us, yes, would like to know if the drip-dropped canvas they own was made by a genius or not. Does it change the value of the canvas? Of course. Why? Because we need the story.

Monday, February 20, 2006

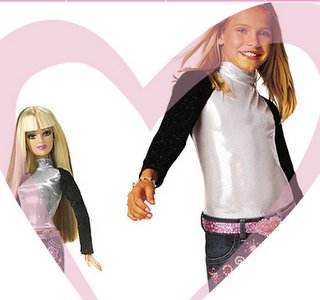

Young Fashion: The Thimble Scandal

Here is something spicy from an area I haven't been paying much attention to - fashion.

I have received the above picture from Maryla Sobek, a friend who teaches at the Fashion School of the UQAM university (huge French-speaking university in Montreal, Canada). The picture, by Anne Marie Sauriol (a student at the university), was going to be a poster for the graduation fashion show (roughly translated, the sign on the side states "Honoring Fashion").

And all hell broke loose.

The director considered it a scandal. Something horribly vulgar and absolutely unacceptable. My friend suggests that the younger generation has a different sensibility, and might see this as a provocation, but not necessarily as a vulgar offense.

There is a large group of people that still find the phrase "fuck you" extremely offensive. Sarah Lucas is not one of them. The amateurs of Sarah Kane's dramaturgy are not among them either. People who experiment don't get offended. They might get bored. Or disappointed. And to me that is more of a risk here.

Bored, because we've seen the middle finger so many times it really isn't anything special.

Disappointed, because we might be expecting something we won't necessarily see on the show.

Now here is my counterargument on both points:

1) This doesn't bore me. Because it has a twist. The thimble - the cap, the condom, the hat, the head, the dot over the 'i', the filter, the creator. The sublimation. The humorist. The hidden treasure. It says "now that I got your attention, come here".

2) Something else this picture says is "We're fed up. And that's our beginning." Which raises expectations. One feels like saying "If you're so tough on everyone else, you better be good". And that's a pretty dangerous zone. Easy to lose.

3) Or is it? I'm not sure the poster is really a statement. It could be seen more as an artsy PR work, Benetton-style. As we know, in its most controversial (and talked about) posters, Benetton chooses topics not necessarily related to the issues it is directly involved with. Rather, it says "we see what you see. we feel what you feel." It speaks to its target group by using empathy. We could say a similar thing is happening here: the students themselves would not be offended by this sort of a poster; it is too common. Just think of all the t-shirts with "bad bitch" written on them. Anyone studying fashion must be aware of what is happening in social behavior, and I suppose it is a good idea to use it, answer it, and then, if you really really want to be an artiste, defy it. So, if this is a statement, I would say it isn't a positive one in the sense that it doesn't actually affirm anything, but rather appeals to a negative attitude that is already present in the public. And then, it uses it, associating itself with the street punk attitude.

Then again, students still have more experience as consumers than creators. So their creation can also be seen as a reaction of a fashion consumer. To what? Well, take Benetton, the edgiest fashion label publicity-wise. The 18-to-20-something year olds of today (including myself) weren't only brought up on Benetton's "ideals". We see the hypocrisy: Benetton had no problem going from this:

to this:

and finally to this:

(2006)

(2006)What are we left with? How can a designer still have ideals, if those ideals are used by marketing specialists in a totally arbitrary way, as it suits the moment? Maybe someone got tired of selling pink dreams and black, satin fairy tales with android proportions? So what is there left to say, what is there left to fight for or invent? I hope, a lot. But just as we needed Artuad's senseless screams to get to a new form of theater, as we needed Cage's silence to get to new music, so in order to get to some fresh, original ideas from time to time we might need a middle finger stuck up high. Hopefully, with a thimble on top.

Light up the night

Have you heard of the LED throwies? It looks like very good "art material", doesn't it?

via

Sunday, February 12, 2006

Make performance art. Be positive.

"At this very moment, Rob Bohn is holding a red jacket in his hand and standing on the corner of 23rd and Broadway near the Flatiron Building.He is excruciatingly cold for he cannot wear his jacket unless he is given an orange.

Simply find a way to get an orange to him and he will thankfully put on his red jacket.

He will be standing on the corner until the sun sets - wearing or not wearing his red jacket. He is depending on you."

This performance, tagged as "wappening", was created by Lee Walton.

It worked:

Friday, February 10, 2006

Cindy Wright: the flesh of paint

Cindy Wright, Skin 2, Oil on canvas (2004)

What I like about these works is that beyond their apparent photo-realism hides a playfulness only possible through painting. It is as if we discovered that beyond the surface of things lie some other levels of things which make them differ. Thus, real skin is different from a photo, a photo is different from a painting. And, mind you, the skin above is different from yours: it hides different shadows.

Different shadows.

It's Jan Fabre. Nice touch.

Thursday, February 9, 2006

Angela de la Cruz at the Culturgest: of guts and canvas

I Suppose Angela de la Cruz's art is usually described as the questioning of painting and stretching the limits of canvas. This seems to me not only obvious, but also not-that-fascinating. On the other hand, if we go beyond this label, we might just find a sculptoric experience truly worthy of participation.

Participation, here, implies that the cold world of de la Cruz's objects has a life of its own; it is a process we can investigate and play with, using the wrecks just as the artist does - to transform our perception of... identity? purity? creation?

The idea of recycling being as old as modern art, it is still a challenge. After Duchamp's and Schwitters' collages, after Fontana's holes and Rauschenberg's manipulations, playing with the very material of a painting - i.e., treating it as a sculpture, might seem absurd.

Apparently, though, there is still a lot to be said. Maybe not "rethinking painting", but using it as any other sculpting material, considering the canvas, the frame, the paint, to be primary matter. The magic word here is convention. If we have a convention, we can express things. We can find ourselves in it and, if we feel the need (?), break it, or at least work our way beyond it. And painting, in its technical perspective, is a beautiful convention. It seems to be there just waiting to be distorted, abused or shred to pieces. So what happens when we consider the canvas a partner of a conversation, a performative matter, one that can act out just as a performer would? We get a world full of characters, semi-characters, objects as real as people.

Angela de la Cruz's most recent exhibition at the Culturgest in Lisbon is a voyage through despair. We begin with evidence of violence. Just as there are no perfect people, no painting here actually has a format. The very presence of dimensions next to the work seems ridiculous - they are living proof of the abandonment of dimensions, of the decay of form. Clearly, decay is far from absence. Decay is the period when something happens, the appearance of a form that comes from itself, not from the essential objects. Or maybe, decay, here, is the discovery of an essence previously unrecognized? The paintings hurt, they grow, they break and they hide. There are two, three works per room, and they sometimes resemble cartoon characters, trying to squeeze into a corner or hide on the ground.

But they can't. They are too easily identifiable, colorful, awefuly, frighteningly three-dimensional. In all their havoc, they cannot escape being themselves. Are they the remnants of something gone? That is the first impression, as their designs still recall some original shape. Look carefully, though. The origin is a myth. The danger, says Wittgenstein, is to try to go before the beginning. The beginning is here, in this state of somethingness, in these monstrous, lonely bodies.

As we move on, we discover a difference: someone has been trying to put things back to order. There are stitches, there is glue, there are screws putting it all back together. But try Heraclitus - you can never step in the same river twice. Try all the contemporary Homers - you never go back home. They look miserable, suffering, and strangely familiar, those paintings and objects (delightful chair on a stool, somewhat too surrealist-like yet attractive double piano) that try to remember what they were, or what they should have been.

We move yet further, to a new level. Here, reality is what it is. Things are affirmed. Old sculptures are recycled in new ones, without trying to find their soul. They live new lives, with all their imperfections, they are clustered and folded, they support others, they are the stuff that things are made of. This clean box has some old canvas sticking out behind it. That white sheet of canvas on the ground hides some old guts, some old stories. And it won't get any better than that. Not here, not in any other real world. So we might just as well find it damn attractive.

Tuesday, February 7, 2006

Find

Monday, February 6, 2006

Map yourself, scratch the object

Everything I have ever... is one of those simple ideas that inspire me in my work.

A large (A1) poster with tens and tens of objects drawn out in silver. Scratch one - and it turns orange, just like in a lottery ticket. You decide if it's everything you've ever lost, found, craved, or just not thought about. I have been doing research on the relationship between the apparent neutrality of objects and the total un-neutrality of identity, and this fits like a glove.

Friday, February 3, 2006

Nam June Paik

Nam June Paik died yesterday.

Few artists deserve the name of avant-garde artists as much as Paik did. His faith in the intimate link between technology and art was one of the fundaments of today's new art. Starting off in the early 60's, he was first more connected to live performance. In the 80's he moved towards large multi-monitor installations. He gave technology a soul. He made art seem fun and intelligent at the same time. At times it seemed as if the fun, experimental and/or esoteric aspects took over, leaving less room for intellectual aspects, but even those works had a power that mesmerized, hypnotized and inspired a whole generation of artists. Actually, come and think of it, he inspired more than a generation, since his works are still seen today as innovative and fresh.

Here is an excerpt from New Media in Art

The (...) 'art'-oriented video histories will usually point to the day in 1965 when Korean-born Fluxus artist and musician Nam June Paik bought one of the first Sony Portapak video sets in New York, and tuyrned his camera on the Papal entourage that day making its way down Fifth Avenue. That, in this view, was the day video art was born. Paik apparently took the footage of the Pope, shot from a cab, and that night showed the results at an artists' hangout, the Cafe a GoGo.

more about Nam June Paik:

Sound Gardens

Here is something that has been around for some time as an idea, with a few small-scale realized projects - but now it seems to be growing quite fast.

The Tactical Sound Garden is an environment (i.e. potentially a physical space of any city) where users of devices such as iPods and other portable sound systems with wireless communication can discover the sounds implanted by others.

In practice this means one walks into a space and hears different sounds. As one moves along, the sounds (songs, noises, voices?) change, new ones appear.

The Tactical Sound Garden [TSG] Toolkit is a vehicle for exploring this via the design of an infrastructure: an open source software platform for cultivating public "sound gardens" within contemporary cities. It draws on the culture and ethic of urban community gardening to posit a participatory environment where new spatial practices for social interaction within technologically mediated environments can be explored and evaluated. Addressing the impact of mobile audio devices like the iPod, the project examines gradations of privacy and publicity within contemporary public space.

Several interesting points about this sort of developments:

- A walkman stops being a synonym of alienation. It can become a shared experience.

- The trust in human goodness is boundless. As the average age of an iPod user (or, what's more significant, a "qualified user") drops, these Gardens, invisible to a common passer - by who might have pu social pressure to keep it tidy, can very well become depositories of some of the most uninspiring sound garbage. ("NOT INCLUDED in the Toolkit are regulations for governing the use (or abuse) of the garden. This is left to the gardeners to sort out. TSGs are intended as self-organizing systems.")

- The audio part of space suddenly becomes a brave new world. It will create specific, isolated communities that are a gem to any advertiser: they have money and time to spend. I wouldn't be surprized, then, if this artistic endeavor soon took on a new twist and became a sort of a commercial radio, where one can discover the wonderful soundscapes for the modest price of having them brought to you by "Chico-Chico, the chocolate that makes it all sound great".

- What exactly is a sound garden? Or rather, what can it be? Are there some possibilities we haven't thought of yet? Rhythms? Conversations? Plays? Games? Dances in public spaces? Lessons? What else?